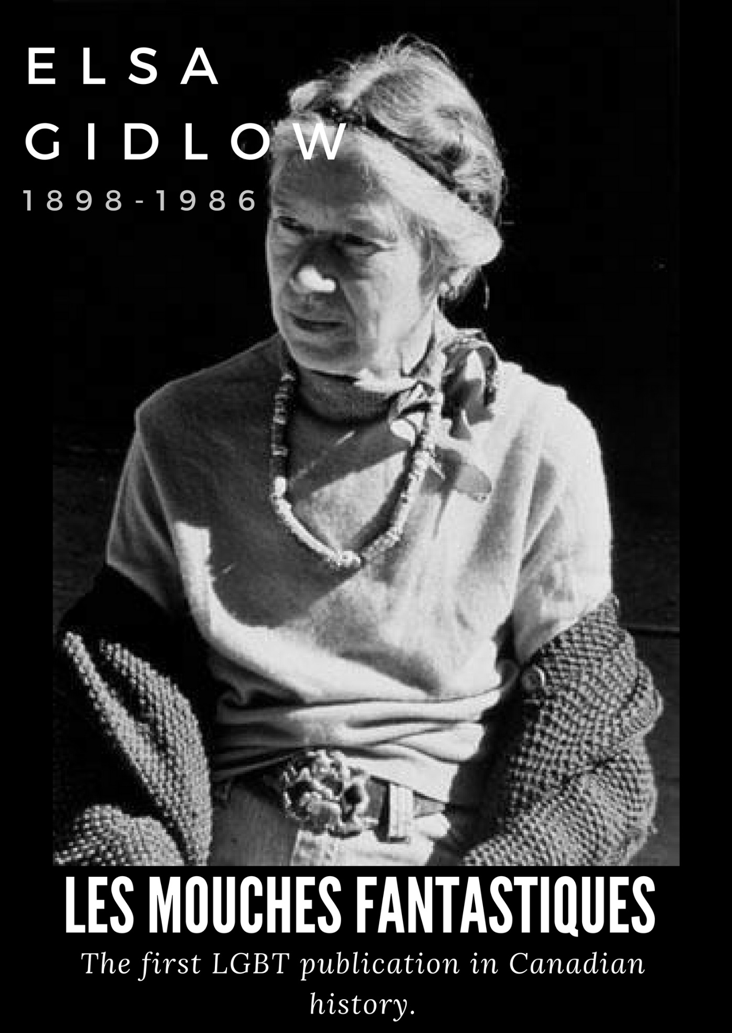

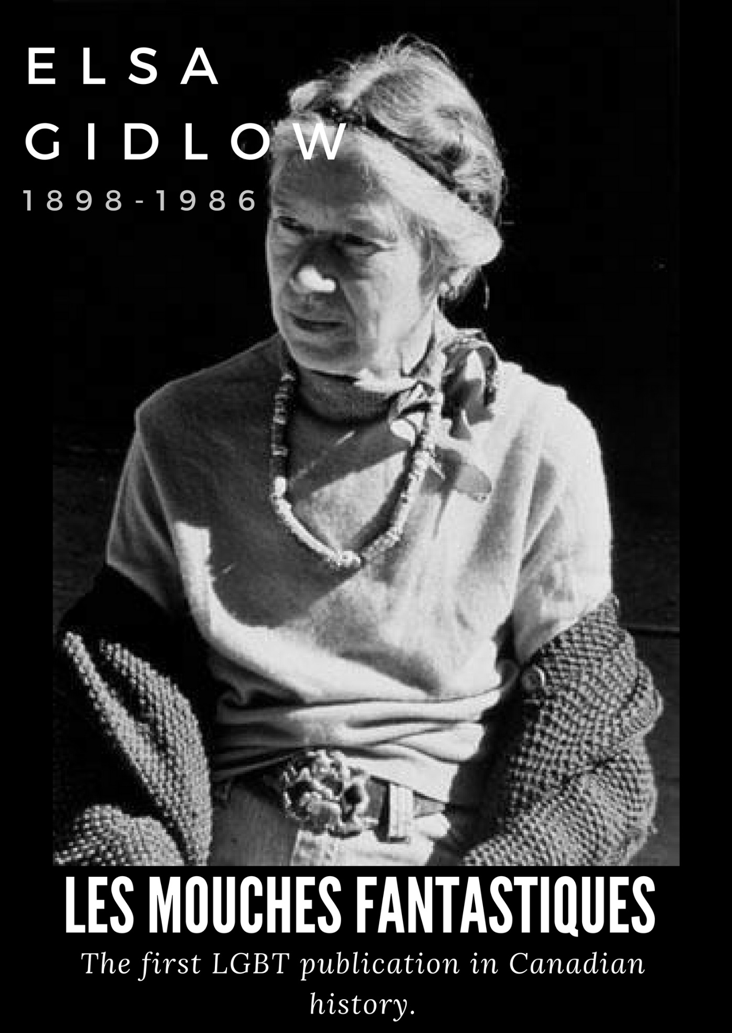

Elsa Gidlow

Introduction:

Elsa Gidlow, originally from Montreal, was an influential poet and writer, also known as a woman “poet-warrior” (Istar Lev 2015). She created the first LGBT publication in Canadian history, Les Mouches Fantastiques that was launched in 1918. With the help of the journalist Roswell George Mills, the publication had been described as an underground magazine, highlighting poetry written by Gildow, politics and gender identity, “…a large component of both the poetry and the politics was an argument for the acceptance of homosexuals” (Hamish 2009). Gidlow, a member of the LGBT community, grew up in a conservative household where sex was taboo, and explained that Mills had opened her eyes to a new outlook on sexuality and poetry. Les Mouches Fantastiques also known as The Fantastic Files, was not widely available outside of Montreal, as Gidlow and Mills moved to New York City in 1920. One copy of the magazine is kept within the Quebec Gay Archives, that will forever mark the first LGBT-based publication introduced in Canada. Overall, the accounts from the LGBT community have been absent within education curriculum, eliminating their stories and voices from historical narrative. Specifically, in the context of Canada, it is important to share queer history in schools, by focusing on both resistance and successes. In the writings of Tom Warner on queer activism in Canada, he states:

Fed up, they decided to take control of their own destinies despite many obstacles. They dared to confront attitudes and deeds that had led to marginalization and social oppression. Individually and as organized communities, they fought back, coming out of the closet, noisily and defiantly, demanding to be both seen and heard, and revelling in their new visibility.” (2002, p.7)

Biography:

Katie Nowell is a student enrolled in the Bachelor of Education program at the University of New Brunswick, originally from Truro, Nova Scotia. She has completed a Bachelor of Arts undergraduate degree from UNB in Fredericton, majoring in Sociology with a minor in French. Inspired by Dusty Green’s presentation in her Social Studies class, she has set off to discover more information about LGBT history in both New Brunswick and Canada overall.

Further Reading:

1. Gidlow, E. (1986). I Come With My Songs: The Autobiography of Elsa Gidlow. San Francisco: Druid Heights Press.

2. Warner, T. (2002). Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

3. Wolf, S. (2009). Sexuality and Socialism: History, Politics, and Theory of LGBT Liberation. Chicago, IL: Haymarket.

Notes: 1) Image of Elsa Gidlow was retrieved from Marin Nostalgia (http://www.marinnostalgia.org/portfolio/druid-heights/)

References

Hamish (2009, November 30). Elsa Gidlow. The Drummer’s Revenge: LGBT history and politics

in Canada. Retrieved from: https://thedrummersrevenge.wordpress.com/2009/11/30/elsa-gidlow/

Istar Lev, A. (2015). Gidlow, Elsa (1898-1986). glbtq, Inc. Retrieved from: http://www.glbtqarchive.com/literature/gidlow_e_L.pdf

Lyons, M. (2015, February 22). Canada’s first gay publication. Retrieved from: https://www.dailyxtra.com/canadas-first-gay-publication-66372

Shanawdithit

Shanawdithit was the last living member of the Beothuk people of what is now known as Newfoundland. The Beothuk population was quickly dwindling due to European disease, settler violence, and restricted access to the sea, which was their food source. Born in 1801, Shanawdithit experienced first-hand the effects that white settler colonialism had on the Beothuks. In 1823, Shanawdithit, along with her mother and sister, was taken to St. John’s by several trappers. It was here that her mother and sister died of tuberculosis, leaving Shanawdithit as the last of her people. Shanawdithit worked as a servant in an English household and later lived with William Eppes Cormack, who founded the Beothuk Institution. It was here that Shanawdithit created drawings and told stories of her nearly extinct people. Prior to this, accounts of the Beothuk were only told through a white settler lens. Shanawdithit was a voice for a people group lost at the hand of settler colonialism and was recognized as a National Historic Person in 2000. The color red ochre was used in the painting to reference the Beothuk’s use of red ochre paint as traditional body paint. This color was used as a part of Beothuk identity and was applied to newborns to welcome them into the world or stripped from individuals as a form of punishment.

Biography: Rebekah Heppner, after completing her undergraduate degree at the University of Manitoba with a double major in history and psychology, moved to Fredericton, New Brunswick and is currently completing a Bachelor of Education degree.

Further Reading:

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/shawnadithit-last-of-the-beothuk-feature/

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/aboriginal/beothuk-disappearance.php

To see Shanawdithit’s drawings: https://www.mun.ca/rels/native/beothuk/beo2gifs/texts/shana2.html

The Komagata Maru

The Komagata Maru: Canada, 1914

Introduction: In 1914, a ship named the Komagata Maru set sail from Punjab, India journeying to Canada. In total, there were 376 males passengers on board; 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus. All of the passengers were traveling to Canada in hopes of gaining Canadian citizenship (Schwinghamer, 2016), but to also challenge Canada’s xenophobic views. Nevertheless, prominent xenophobic mentalities and government policies within Canada lead to the refusal of the passengers to enter the boarders under 2 specific immigration policies (2016). First, Canada practiced the “Continuous Journey” regulation which forced newcomers to travel directly from their place of citizenship to Canada, or they would be denied entry. However, this was impossible for travelers departing from India because direct passage was not an option by boat (Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2018). Second, Canada required passengers to pay a landing fee; however, this fee was typically $25, but Canadian border officials altered this price to $200 for each passenger of the Komagata Maru ship to pay (2016). The Komagata Maru ship’s passengers were forced to live aboard the ship for 2 months while these regulations were negotiated. In the end, only 24 passengers were given permission to remain in the country. The other 352 passengers were guided from Canadian waters, escorted by a war ship, and forced to return to Asia. When the ship arrived in India, the British killed 19 of the passengers, and the remaining men were imprisoned (The National, 2014).

This event, in addition to the similar occurrences that took place before and after in Canada (the Panama Maru), demonstrates a xenophobic mentality that governed Canada and their government policies. This history and the prominent mentalities that existed then, still impact government regulations and mentalities presently in Canada in regards to racialized immigrants. Xenophobia is Canada’s past, but it remains as Canada’s present.

Biography: Shoba Gunaseelan is a student in the Bachelor of Education program at the University of New Brunswick. She is interested in Canada’s history in relation to race and immigration, and how this past narrative impacts present Canada.

Further Reading:

1. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. (2018). Continuous Journey Regulations, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/continuous-journey-regulation-1908

2. Schwinghamer, S. (May 19, 2016). Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21:

Komagata Maru. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7xn8EOcUtU

3. The National. (May 22, 2014). Remembering the Komagata Maru. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhr1Ucr7qlc

4. Kazimi, A. (Producer). (2004). Continuous Journey [Motion Picture]. Canada: TVOntario

Incident at Restigouche

Introduction: Since the horrific experiences that occurred on June 11th and 20th, 1981, the effects still resonate amongst the Mi’gmaq people of Restigouche Reserve in Quebec, known as Listuguj. The fisheries officers and Quebec Provincial Police (QPP) raided Restigouche Reserve and arrested several Mi’gmaq residents as an attack to put an end to all salmon fishing in the Restigouche River. Traditionally, salmon has been a valuable source of food and income for the Mi’gmaq people, and now they were being stripped of their fishing rights by hundreds of armed officers (Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government, n.d.). The officers blocked off the bridge that connects Listuguj to the neighbouring city of Campbellton, NB, used tear gas, and seized fishing boats and fishing nets from the Mi’gmaq people (Canadian History, n.d.).

There are still residents living in Listuguj today that were present for the “Incident at Restigouche” when their community was raided by provincial police. Rene Martin and his partner Joyce Metallic recall the frightful occurrences of 1981 as they were returning from Campbellton with their two children:

“I had my second one in my arms. I remember him pointing a gun at us,” said Metallic. “He pointed the gun and he said, ‘turn around, or I’ll shoot.’”

“People were just standing around doing nothing,” Martin said. “These cops were marching back and forth. Then, once and a while they’d point a finger … and they’d go after somebody” (Staff, 2015).

The events of this Restigouche Raid left the Mi’gmaq people infuriated with the restriction of salmon fishing by the province (Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government, n.d.). Understandably so, since fishing was an innate part of their culture and heritage. In retaliation, residents of Restigouche blocked off roads leading to their reserve to keep the officers out (Canadian History, n.d.). Largely as a result of the efforts of Donald J. Marshall Jr., a Mi’gmaq from the Membertou First Nations, fishing rights were regained by the Mi’gmaq people in Listuguj, allowing them to continue their long-held tradition. He took it upon himself to defend the inherited rights of Aboriginals following being charged with fishing without a license, selling eels without a license, and fishing during the off-season (Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government, n.d.). Alanis Obomsawin has documented an impactful film called “Incident at Restigouche” that gives insight into what transpired and accurately depicts the mistreatment of the Mi’gmaq people living in Listuguj and the restraint they were forced to conform to (Canada, N. F., 1984).

Biography: Michael Methot is a student in the faculty of education at the University of New Brunswick. He is currently an aspiring elementary school teacher with an aim of inspiring today’s youth to seek justice and coexistence in the world.

Further Reading:

1. Canada, N. F. (1984). Incident at Restigouche. Retrieved from https://www.nfb.ca/film/incident_at_restigouche/.

2. Canadian History. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://canadianhistory.ca/index.php/natives/timeline/1980s/1981-the-restigouche-blockade.

3. Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.listugujfisheries.com/content/history.

4. Staff. (2015). Arrested in 1981. Retrieved from http://news.listuguj.ca/2015/06/22/arrested-in-1981/.

Notes:

1) Image of Donald Marshall Jr. fishing, courtesy of Mi’gmaq News 1991, was retrieved from: https://smallscales.ca/2013/04/05/mlf/.

2) Image of troop of Quebec Provincial Police (QPP) raiding Restigouche Reserve was retrieved from: https://boxoffice.hotdocs.ca/images/user/hdff_2315/2016/Incident_at_Restigouche_1.jpg.

3) Image of Mi’gmaq man being arrested for fishing by two Quebec police officers was retrieved from: http://www.isuma.tv/sites/default/files/pictures/incident.jpg.

The Sixties Scoop

LGBTQ+ in the Military

Introduction: On July 26, 2017 President Donald Trump tweeted stating that he was taking action to ban transgender people from the American military despite having the ban lifted by former President Barack Obama (Lubold, 2017). As a result, many individuals were quick to respond to Trump on Twitter by patriotically boasting about Canada’s acceptance for LGBTQ+ peoples. Some tweets include:

“This week president Trump banned transgender people from serving their country. Today, Canada’s Chief of the Defense Staff marched in Pride” (@FuzzyWuzzyTO, August 27, 2017)

“The week when Trump officially institutes transgender ban in military, Canada will roll out gender-neutral passports” (@vfung, August 26, 2017)

“Canada leads while USA moves backwards. Canadian forces aim to improve transgender policy as Trump reinstates ban” (@KristopherWells, July 26, 2017)

Despite the great gains that Canada has made in accepting and celebrating LGBTQ+ individuals both inside and outside of the militarily, the reality is that Canada was not always an inclusive environment, and a recognition of this history is important. In fact, before 1992, thousands of LGBTQ+ Canadian military personnel were discharged as they were considered to be a threat to national security (CBC News, 2017). Not only were these individuals stripped of their livelihoods and unrecognized for their service, but the mistreatment of these individuals had impacts “...on their short – and long – term physical, psychological, and social health” (Poulin, Gouliquer, & Moore, 2009, p. 498). This mistreatment included forcing individuals to watch pornographic videos to test if their pupils dilated when looking at the same gender and forcing them to undergo polygraph tests. This was happening up until 1992 despite the fact that homosexuality had been decriminalized in 1969 (CBC News, 2017).

Although Canada may be working on inclusive gender policies and may have political leaders marching in pride parades, the past will not change. So, before Canadians boast on their acceptance, they must recognize their past to move forward with support, education, and reconciliation.

Biography: Hannah Fournier is a current student in the University of New Brunswick’s Bachelor of Education Program. She also completed her first degree in Leadership Studies at the University of New Brunswick where she had the opportunity to intern at Twitti Primary School in Zambia.

Further Reading:

1. CBC News. (2017). Trudeau is apologizing to LGBT civil servants: Here’s why. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/trudeau-apology-lgbt-civil-servants-military-fired-discrimination-1.4421601

2. FuzzyWuzzyTO. (2017, August 27). This week president Trump banned transgender people from serving their country. Today, Canada’s Chief of the Defense Staff marched in Pride. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/FuzzyWuzzyTO/status/901905114545491968

3. KristopherWells. (2017, July 26). Canada leads while USA moves backwards. Canadian forces aim to improve transgender policy as Trump reinstates ban [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/KristopherWells/status/890395832159133696

4. Lubold, G. (2017). Trump sets military transgender ban. The Wall Street Journal.

5. Poulin, C., Gouliquer, L., & Moore, J. (2009). Discharged for Homosexuality from the Canadian Military: Health Implications for Lesbians. Feminism & Psychology, 19(4) 496-516.

6. Vfung. (2017, August 26). The week when Trump officially institutes transgender ban in military, Canada will roll out gender-neutral passports [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/vfung/status/901519844201332736

Note: The image of Donald Trump was retrieved from http://thehill.com/people/donald-trump

Camp B70

Introduction

Camp B70 is an internment camp located in Minto, NB approximately 30 miles from Fredericton New Brunswick. 711 men and boys were forced to go to this camp, because Canada was afraid. From 1940-1945 the Canadian government forced Jewish men to live at B70 because they thought there may be spies among the Jewish people who moved to Canada. Innocent men were imprisoned for no reason other than fear.

The internees were housed in army barracks and spent their days cutting the 2,500 cords of wood required each year to keep the 100 wood stoves in the camp burning. They wore denim pants with a red stripe on the leg, and denim jackets with a large red circle on the back. There were six machine-gun towers positioned around the perimeter of the camp (MyNB, 2014).

One man, who was only 16 years old at the time stated that “the reason they had a red circle on the back of their jackets was so they could identify you if you ran away, and that it also made it really easy for them to shoot you” (Kauffman, 2013).

This part of New Brunswick is very rarely spoken about. In fact, very few people know that this terrible event occurred.

Biography: Colleen Daly is a student at the University of New Brunswick completing her Bachelors of Education, specifically in elementary. She completed her undergrad in Kinesiology while also being a member of the women’s basketball team at UNB. Born and raised in Hamilton, Ontario, Colleen expresses a strong interest in educating her students on past events that have occurred, so that history does not repeat itself.

For more information on New Brunswick’s Internment Camp:

http://www.nbinternmentcampmuseum.ca

References

http://www.nbinternmentcampmuseum.ca

Internment Camp B70

About the Poster

In the months leading up to WWII, circumstances for Austrian Jews became increasingly dangerous, and 10,000 men and boys were moved to Britain in the Kindertransport effort. Former Prime Minister Winston Churchill became suspicious that there may be spies in the refugees, and sent some to Canada and Australia to be housed in internment camps.

Canada received 700 men and boys who lived at the camp for a year, spending their time chopping chords of wood to keep the 100 wood stoves burning year round. Around the camp’s 22 hectare property were six machine gun towers and 350 armed guards. Prisoners wore denim marked with a red stripe down the pants and a large red circle on the back of the jacket. 10 people died during that year, and in recent years 10 wooden carvings resembling human faces were affixed to trees along a path through the camp site.

Ripples internment camp was closed in 1941 when Sir Winston Churchill realized the detainees could help in the war, and offered a choice of returning to England to join the military or to find a sponsor to remain in Canada. It was only closed for a few weeks in preparation to become a prisoner of war camp, housing German and Italian merchant marines, as well as Canadian citizens who spoke out against the war. This is a little known part of Canadian history, and two significant stories are uncovered here: the first being that Canada basically imprisoned jews during WWII under British orders, and second that Canada imprisoned its own citizens for being against the war. This paints Canada in a very different light than the traditional conceptualized Canada that is taught in schools.

About the Artist:

Travis MacLean is currently enrolled in the elementary stream of the BEd program at the University of New Brunswick. He studied Kinesiology at Dalhousie University from 2007-12 and then worked as a Personal Fitness Trainer for 3 years before travelling to South Korea to teach English for one year and returning to the maritimes to pursue education.

Additional Readings:

https://mynewbrunswick.ca/internment-camp-b70/

http://www.metronews.ca/news/canada/2013/08/03/internment-camp-little-known-in-new-brunswick.html

http://www.nbinternmentcampmuseum.ca/

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/170785

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/08/03/welcome-to-internment-cam_n_3699703.html

Protest in St. John

In April, 1916, the Black community of Saint John became embroiled in the first human rights protest to occur within the province. Just a few years after the start of the first World War, the film “A Birth of a Nation” was being shown all over the United states, and was generating nationwide controversy. The plot of the film was built around two

families who found themselves on opposite sides of the American Civil War, and the reconstruction period following the conflict. The film was based on Thomas Dixon’s book and play The Clansman, and portrayed the Ku Klux Klan as heroic actors, while Black, Southern Americans were stereotyped and demeaned throughout the film (NBBHS, 2018).

The film was slated to be shown at the Saint John Opera House Theatre in early 1916, and, starting in March of that year, the Black community in Saint John began protests against the showing of the film (NBBHS). At the head of the protest movement was Reverend J. Harrison Franklin (Thelostvalley.blogspot.ca, 2018). The protests began with raising awareness of the film and it’s anti-Black portrayals at St. Paul’s

African Methodist Episcopal Church at the corner of Pitt Street and Queen Street.

Franklin also wrote letters of protest to local newspapers, afterwards raising funds by appealing to the Evangelical Alliance, using them to purchase the services of attorney J. A. Barry. Together, they met with the mayor of Saint John and “political appointees on the Board of Censors” (Thelostvalley.blogspot.ca, 2018). In his meetings, Franklin

raised several arguments, including the damage that would be caused to relations between Whites and Blacks. In response to the protest, the Censor Board agreed to view the film another time, along with Franklin, Barry, and Attorney General J. B. M Baxter. Despite these efforts, the film was shown in early to mid 1916.

Biography Hendrik Vlaar is a pre-service teacher at the University of New Brunswick.

References

New Brunswick Black History Society. (2018). Historical Sites. [online] Available at: https://www.nbblackhistorysociety.org/historical-sites.html [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

Thelostvalley.blogspot.ca. (2018). THE BIRTH OF A NATION - D. W. Griffith's epic was a morale booster in wartime Canada. [online] Available at: http://thelostvalley.blogspot.ca/2016/09/the-birth-of-nation-d-w-griffiths-epic.html [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

Thomas Peters

Remember Resist Redraw Poster - Black Loyalists - The Story of Thomas Peters

Thomas Peters was born into a wealthy family in Nigeria but as a young man he was captured and taken to North Carolina where he was forced into slavery. In 1775, a proclamation declared that Black Loyalists who fought for the British during the American Revolutionary War and were owned by rebels would be granted freedom post-war. Thomas Peters escaped and joined the Black Loyalists. After the war, the British evacuated Thomas Peters to Nova Scotia along with many other Black Loyalists. The British did not follow through on their promises of land, provisions and freedoms to many of the Black Loyalists and Thomas Peters petitioned on their behalf for 6 years. As an advocate for the Black Loyalists, living in Saint John, Peters raised funds to go to England to meet with the King but ended up meeting with men from the Sierra Leone company that had been formed to resettle ex-slaves to West Africa. He arranged for himself and many other Black Loyalists free transportation to West Africa where they hoped for a better life and fair treatment. In 1792, almost 1200 Black Loyalists were transported from Halifax to West Africa where they founded Freetown. Although Thomas Peters passed away from the fever shortly after the arrival; he is regarded as a leader, pioneer and one of the founding fathers of Sierra Leone.

About the Author: Robin Buckley is a BEd student at the University of New Brunswick specializing in Elementary Education. She was born and raised in the Saint John area and never heard about the Black Loyalists until researching for this poster.

Resources used to write this article and make the poster for further reading:

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peters_thomas_4E.html

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/thomas-peters/

http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/people/secular/peters.htm

The Nova Scotia "Home for Coloured Children"

Introduction: 1921 was the year in which The Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children opened its doors to African Nova Scotian children who no longer had a home to call their own. While there were many orphanages available in the province for white children in need of care at the time, black children were not afforded the same opportunities. For this reason, the seemingly segregated Home was created out of necessity, not regarding itself as “separate but equal”, but rather “separate or nothing” (Saunders, 1994). While the intentions in the formation of the Home were considered respectable at the time, the legacy of the orphanage that existed well into the 1980s is one of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse (The Canadian Press, 2014), a legacy which is echoed in a province recognized for its history of systemic and institutionalized racism (Bundale, 2018). In 2014, a $34 million class action lawsuit was settled between the province of Nova Scotia and the survivors of the abuse that existed in the Home, drawing an end to a legal battle that lasted for 15 years (The Canadian Press, 2014). In light of this settlement, Nova Scotia premier Stephen McNeil issued an apology to all former residents of the Home, declaring "It is one of the great tragedies in our province's history that your cries for help were greeted with silence for so long... Some of you had said that you felt invisible. Well I want to say to you today you are invisible no longer. We hear your voices and we grieve your pain and we are sorry” (Doucette, 2014).

A Restorative Inquiry has since been launched by the government in conjunction with former residents of the Home in the effort to not only understand what events transpired in the Home, but why they occurred and why this is important for every Nova Scotian and Canadian to recognize. The inquiry is restorative in nature as it promotes a community of healing through sharing circles in which every former resident’s voice is heard and valued. It looks to address the past in order to create purposeful change for the future in the province (Restorative Inquiry, 2018). As the report states, "Understanding and addressing historic and ongoing impacts of systemic racism on African Nova Scotians, while necessarily rooted in both past and present experiences, is a critical lens necessary to create meaningful change for the future” (Restorative Inquiry, 2018).

Biography: Kennedy Graham is a current Bachelor of Education candidate at the University of New Brunswick, and recognizes that she lives and studies on unceded and un-surrendered Wolastoqiyik territory. She has recently graduated with her Bachelor of Science with a major in biology and a minor in psychology from Memorial University of Newfoundland. She is very concerned with promoting positive social and environmental change in the future generations of students that will enter her classroom.

Further Reading:

1. Bundale, B. (2018, January). New report challenges Nova Scotia to confront systemic racism. CTV News Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/new-report-challenges-nova-scotia-to-confront-systemic-racism-1 .3756604

2. The Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. (n.d.). Retrieved February 12, 2018, from https://restorativeinquiry.ca/

3. Saunders, C. R. (1994). Share & Care: The Story of the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing.

Bibliography:

Bundale, B. (2018, January). New report challenges Nova Scotia to confront systemic racism. CTV News Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/new-report-challenges-nova-scotia-to-confront-systemic-racism-1.3756604

The Canadian Press. (2014, July). Survivors of alleged abuse at orphanage win settlement. Macleans. Retrieved from: http://www.macleans.ca/news/need-to-know/survivors-of-alleged-abuse-at-halifax-orphanage-win-major-settlement/

Doucette, K. (2014, October). Premier Apologizes for Abuse at Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. CTV News Atlantic. Retrieved from: atlantic.ctvnews.ca/premier-apologizes-for-abuse-at-nova-scotia-home-for-colored-children-1.204 8496.

Gorman, M., MacIntyre, E. (2015, June). ‘A long journey’ to Colored Home inquiry. The Chronicle Herald. Retrieved from: http://thechronicleherald.ca/metro/1292776-%E2%80%98a-long-journey%E2%80%99-to-colored- home-inquiry

The Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. (n.d.). Retrieved February 12, 2018, from https://restorativeinquiry.ca/

Saunders, C. R. (1994). Share & Care: The Story of the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing.

New Brunswick Colonialism

The topic I chose is New Brunswick Colonialism. Specifically, I looked at Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) Communities from the past and from the present.

There is evidence that shows human beings lived in the maritime provinces of Canada for over 10,000 years. However, European and other settlers have only been here for approximately 500 years. This means, that the Eurocentric culture has only been in, what is now Canada, for less than 5% of its existence. Prior to this colonization, Wolastoqiyik and their allies Mi’kmaq (East) and Passamaquoddy and Penobscot (West) were the only people who inhabited the area. During this time, Wolastoqiyik were hunters and fishers. They relied heavily on nature to survive. They lived in wigwams in walled villages and only used natural products (wood, stone, etc.) to build and make tools. The main language spoken was the Wolastoqiyik language- which is also referred to as Maliseet.

However, in the 1700’s and 1800’s when Settlers moved over, everything changed. The colonial government created what are called reserves where Aboriginal individuals lived. In New Brunswick, there are only 15 reserves. European and other countries began to take over Wolastoqiyik land, leaving Wolastoqiyik with minimal left. This affected their lives majorly.

My poster outlines the areas that Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq people currently reside. It represents their past freedom and the current prejudice they face today. According to a 2017 statistic, there are approximately 16,123 First Nations living in New Brunswick. Out of those, 9,732 live on reserve and 6,391 live off reserve (GNB).

Biography: Mackenzie Albert is a University of New Brunswick student completing her Bachelor of Education specializing in the Elementary stream. She previously completed her Bachelor of Arts with a major in Psychology at UNB. She was born and raised in Moncton, New Brunswick, but moved to Fredericton five years ago to pursue her education.

Additional Resources: Some resources that are available for further information include:

· http://genealogyfirst.ca/first-nations

Notes:

· Information and Photo Retrieved from Government of New Brunswick: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/aboriginal_affairs.html

· Information Retrieved From: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/maliseet

Indigenous Peoples' Wartime Service

Introduction:

Over 3000 Status Indians, including 72 women, voluntarily enlisted in World War II. This number would no doubt increase if the figures included Inuit, Métis, and other Indigenous people. 200 of the identified Indigenous soldiers had died in service and there were at least 17 decorations for bravery in action rewarded (Veteran Affairs Canada, n.d.; Francis, Jones, Smith, & Wardhaugh, 2012, pp. 356-357). Furthermore, back at home, Indigenous Peoples helped out significantly by giving monetarily. It added up by the end to a contribution of more than $23,000 coming from Native bands and an additional unknown amount given to the Red Cross, the British War Victims Fund, the Salvation Army and other charities involved in the war effort (CBC news online, 2006).

While they were serving, the overall sentiment from Indigenous soldiers were that they were treated as equals. Charles Bird exclaimed “‘no such thing as discrimination… Everybody is a brother to you that’s the way it was”’ (Lackenbauer, Moses, Sheffield & Gohier, n.d. p.154). However, as Howard Anderson said from Punnichy, Saskatchewan: “‘it was the coming back that was the hard part. That’s where the problem was. We could never be the same yet we were the same in the Army. When [we came back we] were different’” (Lackenbauer et al., n.d., p.154).

When the soldiers returned, they were not offered the same gratitude or given the same benefits as other veterans. Rather, the Status-Indian population experienced even greater oppression. There was $6,000 in Veteran Land Act Loans that Status Indian veterans were not able to obtain. Those on reserves were given grants to use towards their farms, but selling and making a living off of their farms was made very difficult by systemic factors. They also could not access the same services as other veterans such as information, benefits, and counselling because of confusing bureaucracy. There were three federal bureaucracies in overlapping jurisdictions to navigate, whereas other veterans had direct counselling from Veteran Affairs agents (Lackenbauer et al., n.d., pp. 154-155).

In addition, there were many arbitrary wartime measures that took place involving Indigenous People: seizure of reserve lands, moving of populations of reserves, and revisions of band memberships. Lastly, they continued to be wards of the state and were denied the right to vote (Francis et al, 2012, p. 357). Overall, Indigenous veterans wanted to be acknowledge for their voluntary contributions and were very proud of their volunteerism. However, the war years created more oppression and demoralized Indigenous People in a profound way.

Biography:

Sarah DeMerchant is a pre-service teacher at the University of New Brunswick. She is working towards a specialization in exceptionalities and has a strong interest in contributing to the field of inclusive education.

Further Reading:

In Depth Aboriginal Canadians: Aboriginals and the Canadian Military. (2006, June 21). Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news2/background/aboriginals/aboriginals-military.html

Francis, R. D., Jones, R., Smith, D. B., & Wardhaugh, R. A. (2012). Destinies: Canadian history since confederation (7th ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson Education Ltd.

Lackenbauer, P.W., Moses, J., Sheffield, R.S., & Gohier, M. (n.d.). A commemorative history of Aboriginal People in the Canadian military. National Defence, Art Direction. Retrieved from http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/pub/boo-bro/abo-aut/chapter-chapitre-05-eng.asp

Veterans Affairs Canada. (n.d.). Indigenous People in the Second World War. Retrieved from http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/historical-sheets/aborigin

Veterans Affairs Canada. (n.d.). Indigenous Veterans. Retrieved from http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/indigenous-veterans

Veterans Affairs Canada. (n.d.). Illustrations. Retrieved from http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/indigenous-veterans/illustrations

Notes:

Image representing each of the three main Indigenous groups was created for the Calling Home Ceremony in 2005 which was a Aboriginal Spiritual Journey to honour the Indigenous war dead. This image was retrieved from http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/indigenous-veterans/illustrations

Image of war recruits before they left for Great Britain from the File Hills community in Saskatchewan with the elders, family members, and representative from the Department of Indian Affairs. Image retrieved from http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/historical-sheets/aborigin from the Library and Archives Canada PA-66815.

Middle Island

Introduction: Middle Island is a popular, well-known attraction in Miramichi, New Brunswick but before it was an Irish Historical Park, it was a quarantine station for Irish Immigrants who had developed Typhus and Scarlet Fever while fleeing from their homeland during the Potato Famine in 1847.

People were travelling on a ship called Looshtauk from Liverpool to Quebec, and when many people onboard began to get ill, a decision was made to stop at the closest port for medical assistance. After stopping in Miramichi and speaking to officials at the marina, they were instructed to dock at Middle Island and use the land as a quarantine station (Middle Island Miramichi, n.d.).

Dr. Vondy, a young doctor who has just started his medical practice in the former town of Chatham (now Miramichi City), decided to close his office so he could go to the island and fully commit his time to the ill individuals there. In doing so, he risked his own health and life, and eventually died shortly after his arrival (Middle Island Miramichi, n.d.).

The Looshtauk’s voyage started with 462 people, 146 people died on the ship, 316 were let off at Middle Island for medical treatment and of those 316, 96 people lost their battles with their illness on the island, 53 were able to continue with their travels on to Quebec, and the remaining 167 were eventually able to be discharged into the Town of Chatham (Middle Island Miramichi, n.d.).

Middle Island was purchased by the New Brunswick government in 1950 and a causeway was built from the mainland for easy access in 1967. Today, Middle Island is a park than many people from near and far visit. The walking trails are enriched with plaques that tell the stories of many years ago and there is an interpretive museum for people to learn more about its history. Middle Island is also used as a popular fishing spot and a place where the city hosts special events.

Biography: Kim Bourque is an Education student with a concentration in Early Childhood Education at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton. Before entering the Bachelor of Education program she obtained her Bachelor of Arts with a major in Psychology in 2017 from UNB.

Further Reading:

1) Daley, C. (n.d.). Quarantine stations - Middle Island. http://newirelandnb.ca/middle-island/

2) Daley, C., & Springer, A. (2002). Middle Island: before and after the tragedy. Miramichi, NB: Middle Island Irish Historical Park.

3) Middle Island Miramichi. (n.d.). https://www.middleislandmiramichi.com/

4) Swiggum, S. (2005). New Brunswick - Miramichi & Chatham - Middle Island. http://www.theshipslist.com/1847/Miramichi.shtml

Notes:

1) History of Middle Island obtained from: https://www.middleislandmiramichi.com/

2) Photo of Middle Island on poster obtained from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/16372470@N00/2539018391

Abegweit

Poster Information:

Abegweit is actually a term to describe Prince Edward Island. Although most islanders are the descendants of Europeans, the island’s first residence however were the Mi’kmaq people. They landed in the province about 2000 years ago. The originally named the Island “EPEKWITK” which translated to “cradled on the waves” which the European settlers pronounced as Abegweit. There are still a first nations M’ikmaq communities going strong within different regions of Prince Edward Island like Rocky Point and Lennox Island for example. I believe this is extremely important for us as P.E.I residence to know about this vital piece of history on how this province was discovered. As sad as it is to say I do not feel that enough of this Island’s residence are aware of this.

This was very interesting for me to research being a resident of Prince Edward Island and was quite eye opening. Even growing up, I have heard the word “Abegweit” used so many times in the province of P.E.I for everything as summer camps, entertainment groups, clothing, stores, and even boats. Admittedly I never ever understood the meaning or history behind it and it’s quite embarrassing to have only discovered the meaning behind the word now. It was a very meaningful piece of P.E.I history for me to discover and I’m quite grateful that I was given the hint to learn more about this.

Additional Information:

For more research on the history of P.E.I and the Mi’kmaq people you can visit:

Tourism PEI/History:

https://www.tourismpei.com/pei-history

About Mi’kMaq confederacy:

UPEI Libraries Mi’kmaq History:

https://library.upei.ca/mi%27kmaq/pei

Biography:

My name is Jamie Buote and I am currently enrolled in the education program offered at UNB, Fredericton. I grew up in Prince Edward Island where I was very interested in sports and music and moved here for my undergrad in Kinesiology in 2012. Since I am from Prince Edward Island I thought it would be interesting to remember, resist and redraw a piece of history from my home province. The event or topic that I have chosen revolves around the word Abegweit and what it means to P.E.I. and its history.

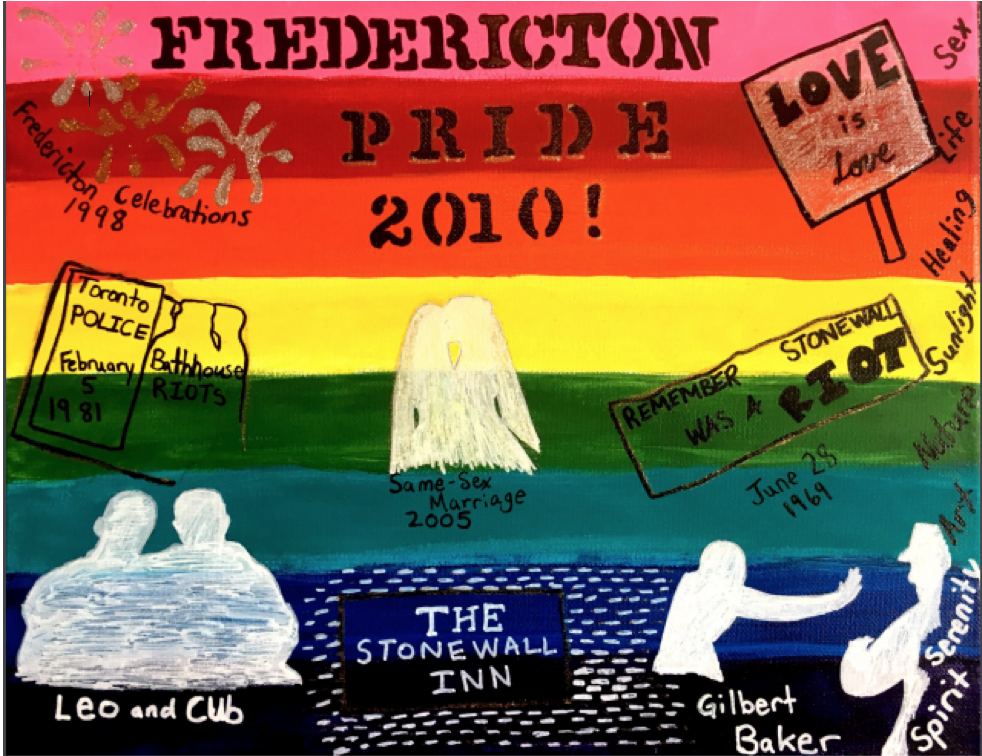

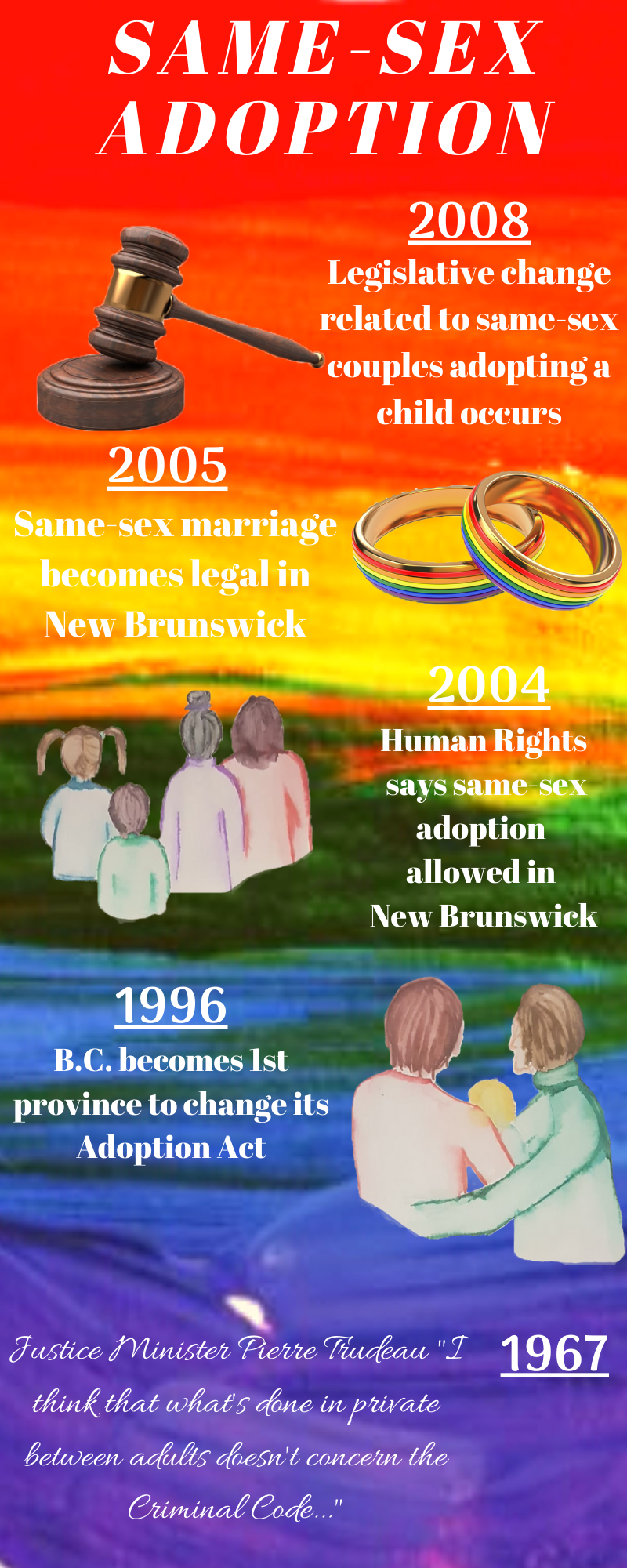

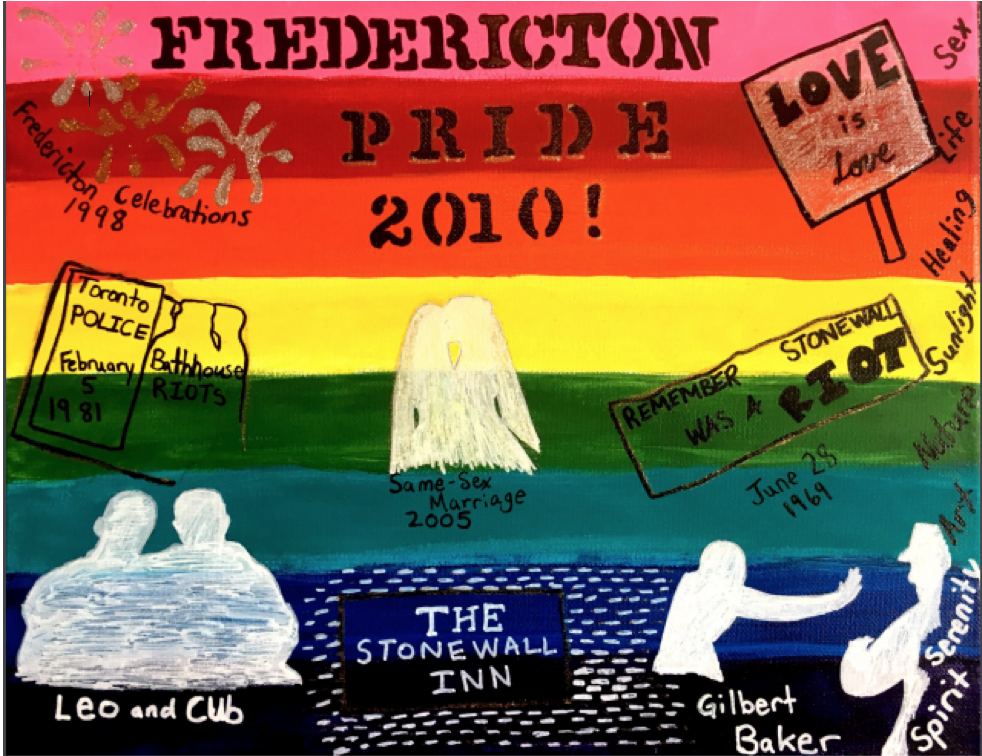

PRIDE

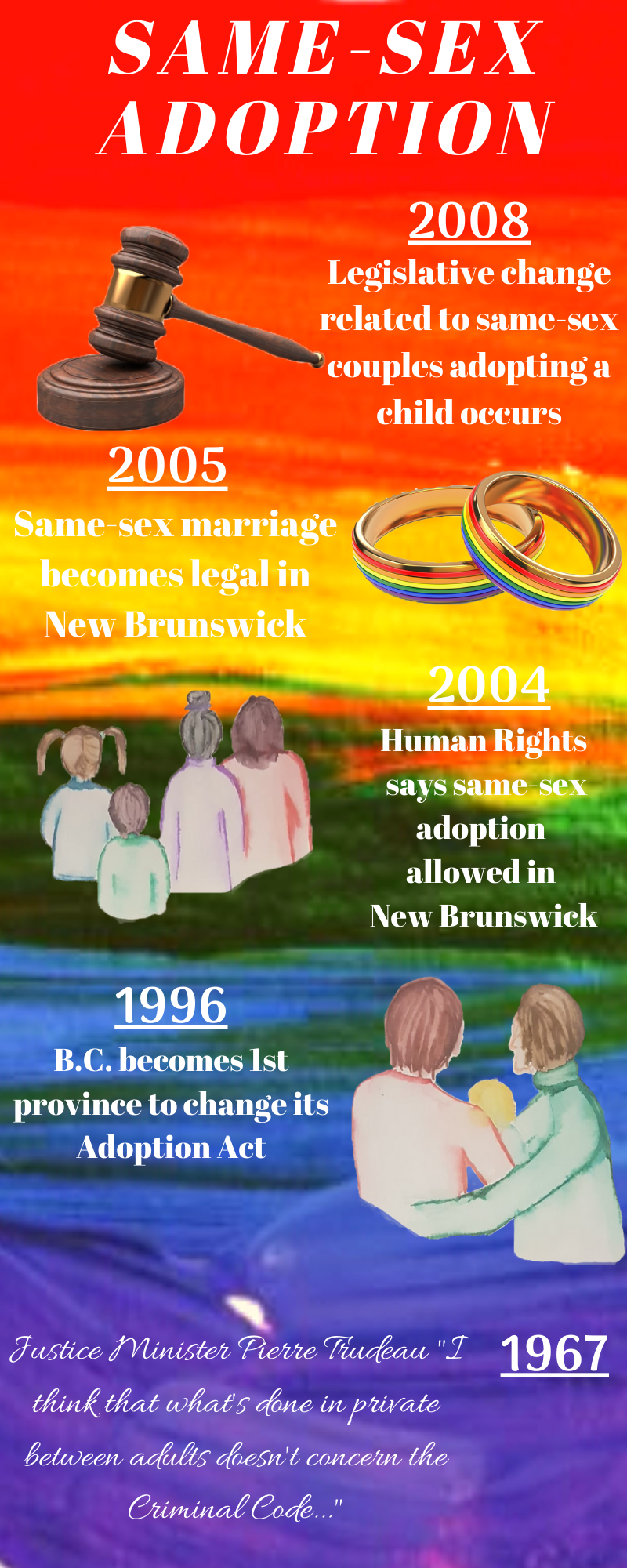

My poster is called “Bringing PRIDE to Fredericton” it depicts the influential LGBTQ movements and laws along with the violence, resistance and love that made it possible for the Pride march to be celebrated in Fredericton.

For a long time being gay was punishable by death, forcing people like Lenard Keith to leave his partner and his home in rural New Brunswick in the early 20th century. It was not until May 1969 that gay sex was decriminalized, helped by the reform demanded by the new Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Later that same year at The Stonewall Inn in New York City, one of the few place where the LGBTQ community could be themselves, was raided by the police. On June 28th the police started arresting the patrons, but the community gathered and rioted against it. The crowd grew with members of the LGBTQ community and their Allies and the riot lasted three days. This violence was the spark that made it possible to start the tradition of the PRIDE march each year, to remind society that everyone deserves the same rights. In Toronto on February 5th 1981, Canada had its own version of Stonewall. It was the Toronto Bathhouse Riot. A popular bathhouse in Toronto was raided by the police and people were arrested for indecency, and the community rioted again it. These types of raids continued across Canada as recently as 2002.

These movements of resistance have led to legal movements in New Brunswick, sexual orientation was protected in 1992, Fredericton started hosting LGBTQ events in 1998, the first same-sex marriage happened in 2005 leading to the first PRIDE March celebration in 2010. It is an event that can now be a celebration for how far the LGBTQ community has come, a symbol of resistance against hostility, and a voice for those who have been lost or silenced for loving who they love and being who they are.

Biography:

I am Madeline Raaflaub, I am from Ontario, but recently moved to Fredericton. I am pursuing a Bachelor of Education at the University of New Brunswick and I will be teaching Grade 1 next year overseas.

Further Investigations:

Rau, Krishna. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights in Canada”. Historica Canada, 2015, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-rights-in-canada/

“Remembering Stonewall.” Stuff You Should Know. From How Stuff Works, 27 June 2017, https://www.stuffyoushouldknow.com/podcasts/remembering-stonewall.htm

The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, 2017, https://clga.ca/

Government of Canada. “Rights of LGBTI persons”, 2017, https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/rights-lgbti-persons.html

The background is based of the artwork of Gilbert Baker, who revealed this flag at the New York Pride in 1978.

The image of Leo and Cub is based on one of the photos collected by the New Brunswick Queer Heritage Initiative.

The image of the Toronto Bathhouse Riots is based on a phot taken by Frank Lennon.

Aida Flemming

Aida Maud Boyer McAnn Flemming (7 March 1896 – 25 January 1994)

A search through Wikipedia’s listings of notable people from New Brunswick details the names, dates of birth and death (if applicable) and the accomplishment they are famous for. New Brunswickers such as Sean Couturier, (NHL Player), Stompin’ Tom Connors (musician), Molly Kool (First Female Sea Capitan),and Aida Flemming, identified as being famous for being a Premier's wife and under the “other” column again listed as wife of Hugh John Flemming (Wikipedia, 2017).

Aida Flemming had Bachelors of Arts from Mount Alison, a Certificate of Education from the University of Toronto, and Masters in English from Columbia University which she received by 1930 (Driver, 2008, p. 61) Her marriage to Hugh John Flemming was her third marriage, with the previous two ending in divorce.

In 1959 at the age of 63, Aida Flemming founded the Kindness Club, the principals of which, were based on the works of Dr. Albert Schweitzer which taught children to value all creatures great and small. At the peak of its existence the Kindness Club had chapters in 22 countries(Government of Canada, Governor General, Honours 2009). Aida Flemming’s works inspired Alden Nowlan’s poem “An Ode for Aida Flemming”(wikiipedia, Aida Flemming, 2017).

In 1978 Aida Flemming was invested as a Member of the Order of Canada for her founding of the Kindness Club along with her many other contributions (Government of Canada, Governor General, Honours 2009). Aida Flemming, was more than a wife.

Biography: Katie Despaties, graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1999 with her Bachelor of Arts Degree, has travelled extensively, past and present volunteer for many organizations and boards, previously employed in Regulatory Compliance and is currently registered in the University of New Brunswick’s Bachelor of Education Program. She is a happily married mother of three - also more than a wife.

References

Driver, E. (2008). Culinary landmarks: a bibliography of Canadian cookbooks, 1825-1949. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Retrieved January 14 2018. https://books.google.ca/books?id=B40ZbsCTjx4C&pg=PA61&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=aida%20mcann&f=false

Government of Canada, Office of the Secretary to the Governor General, Information and Media Services. (2009, April 30). Honours Order of Canada. Retrieved January 14, 2018, from http://archive.gg.ca/honours/search-recherche/honours-desc.asp?lang=e&TypeID=orc&id=542

Aida McAnn Flemming. (2017, September 12). In Wikipedia, the Free Encycopedia Retrieved January 21, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aida_McAnn_Flemming#cite_note-14

List of people from New Brunswick. (2017, December 13). In Wikipedia, the Free Encycopedia Retrieved January 14, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_people_from_New_Brunswick

Images Courtesy of New Brunswick Archives

For further reading:

New Brunswick Archives has a large collection of Kindness Club documents, pictures, and files including

information on Aida McAnn Flemming

The Culinary Landmarks book by E Driver includes biographical information on Aida Flemming

Aida Flemming has a limited internet footprint

Maria Bochkareva

Maria Bochkareva

Born in 1889 in Siberia to abusive alcoholic parents, Maria Bochkareva’s early life was filled with poverty and violence. By 15, Bochkareva had left home and married her first husband, Afansi Bochkarev. He too, was physically abusive. This continued until the night Bochkareva threatened him with an ax and left town.

It was right after Bochkareva left her second abusive husband that she learned of Russia’s war with Germany. She immediately signed up to become a soldier. Though the commander refused at first, Bochkareva eventually received permission directly from the tsar. She was allowed to join and her company was soon sent to the front lines in Poland.

It was here that Bochkareva first demonstrated her courageousness as a soldier. On their first advance, her company found themselves caught between barbed wire in front of them and still-advancing Russian soldiers to their rear. Ordered to retreat, only 48 returned to the trenches. That night, Bochkareva went back over the top and retrieved solider after wounded soldier from the battlefield. Working until dawn, she recovered 50 of her comrades.

In the course of her career, Bochkareva would, time and time again, risk her own life in order to pull wounded soldiers to safety. She was injured several times, and though she was eventually quite decorated and promoted to the rank of sergeant, Bochkareva was also denied honours for which she was recommended because she was a woman.

In the wake of the February Revolution of 1917, the Russian troops were beginning to fall apart. Bochkareva, in an attempt to shame the male soldiers into continuing to fight, proposed the creation of an all-female Battalion. The Provisional Government approved, and nearly 2000 women signed up. Under Bochkareva’s iron-fisted leadership, most of these women either left or were sent home until only 300 remained. These women trained 16 hours a day for a month before joining the front lines.

In their first offensive, the soldiers were given orders to advance, but many of the male soldiers refused and instead declared their neutrality. Eventually, most of the male officers took up rifles and asked to join Bochkareva’s battalion. The women and officers went over the top together, and soon more than half of the male soldiers joined them. They suffered heavy losses and were forced to retreat, but had shown that they were battle-brave.

Unfortunately, the shifting political climate in Russia meant that soon the Battalion of Death was recognized as a type of propaganda that supported a war the Bolsheviks deemed imperialist. Russian soldiers turned against them, and after 20 of her soldiers were lynched, Bochkareva dissolved the battalion.

Though we often don’t remember them, female soldiers have played important roles in armed combat throughout history. By studying their stories, we are able to complicate and enrich our understandings and memories of war, politics, gender roles and expectations, violence, and social class.

What we do and don’t remember does not speak to what happened in the past, but it does attest to what is happening now. The current widely-accepted historical narrative asserts that it has only been recently that women participated in active combat roles. What does this preference say about our society?

Works Cited

Atwood, Kathryn J. Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014. books.google.ca

Cook, Bernard A., ed. Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia From Antiquity to the Present. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, 2006. books.google.ca

Kihntopf, Michael P. “During World War I, Russian Lieutenant Maria Bochkareva Forged the

Women’s Death Battalion.” Military History 20.2 (2003): 22 - 23, 76.

Biography

Rachael Lawless is a pre-service Elementary school teacher with a background in social memory studies and a black belt in Karate. She loves dinosaurs, archaeology, latkes, good weather, and a great story.

Sarah Edmonds

Sarah Edmonds lived an incredible life! She was born Sarah Emma Edmondson in 1841 in rural New Brunswick in the dead of winter to parents who desperately wanted to have a healthy son.[1] She did not want to live the standard life of a farmer’s wife and fled her family’s homestead and the arranged marriage that her father had planned for her in 1857.[2] She changed her name to hide her female identity, while selling bibles door to door in Moncton and parts of Nova Scotia. Edmonds was vehemently against slavery and as a staunch Christian, she wanted to help the Union forces. Edmonds changed her name once again to Franklin Thompson and was mustered into the 2nd Michigan Infantry as a male nurse, a mail carrier, and supposedly a spy for the Unionists.[3] After contracting malaria, she was denied furlough and thusly “Franklin Thompson” was charged with desertion because Edmonds needed medical attention as a woman. Eventually she wrote and published her memoirs, married a man she loved, had five children, returned to New Brunswick, and eventually was granted a veteran’s pension on behalf of “Franklin Thompson”. She is the only woman member of the Grand Army of the Republic, buried with military honours in Texas.[4] Sarah Edmonds’ story is that of a rebellious, strong, fearless, determined rural New Brunswick woman. Her life and story are significant for her tenacity and obvious love of life and adventure in mid to late 19th century Canada.

Heather-Ann Caldwell is a Pre-Service secondary teacher. She can be found with her nose in a history book, loves listening to obscure French songs, and is looking forward to her 8 week practicum with her Grade 8 French Immersion students in Fredericton, New Brunswick.

Further Reading

Edmonds, S. Emma. Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-Fields. 1865.

https://www.civilwar.org/learn/biographies/sarah-emma-edmonds

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sarah-edmonds-frank-thompson/

[1] “Sarah Edmonds (Frank Thompson),” Edward Butts, May 26th 2016. URL:http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sarah-edmonds-frank-thompson/, Accessed January 30th 2018.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Sarah Emma Edmonds,” Jone Johnson Lewis, April 13 201. URL: https://www.thoughtco.com/sarah-emma-edmonds-frank-thompson-3528659, Accessed January 30th 2018.

[4] Ibid.

Immigration Policy Biases

The Insidious Bias Behind Immigration Policies

Introduction: Canada has welcomed immigrants, with restrictions, to an increasing number advantaged and disadvantaged populations through its permeable borders. Through the course of Canadian immigration history, there have been both explicit and underlying motives for this moving permeability. In highlighting the 1950s resettlement of Palestinian refugees, media coverage and federal polls regarding attitudes towards economic immigration and refugee acceptance, and the provincial history of accepting refugees, this poster attempts to show that there is frequently a larger external bias in the accepting and dispersing of immigrants throughout Canada.

Prior to the 1951 United Nations convention relating to the status of refugees, Canada’s immigration policy, particularly that of Pier 21, served largely to promote a population growth of European-born Canadians. However, after this larger agreement from the United Nations, and perhaps pressure from neighboring countries:

IN THE SUMMER of 1955, the Canadian government took the “bold step” of admitting displaced Palestinian refugees from the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. Canadian officials believed that alleviating the refugee problem in the Middle East would help in furthering regional stability. The resettlement scheme remained a politically sensitive issue as Arab governments protested against what they perceived as a Zionist plot to remove Palestinians from their ancestral land. (Jan Raska, 2015, 445)

Prior to the Immigration Act of 1952, immigration policy restricted the settlement of non-European immigrants into Canada. Racial terms were frequently used in immigration documents. Jan Raska puts forward the point that admitting these refugees constituted an affirmation of the Israeli takeover of Palestinian ancestral land. This governmental position contrasts with polls taken at the time, which indicate that Canadians remained neutral on the position, with approximately 4% being more favorable to the Arab cause. He also argues that this immigration served as a human experiment of the implications of accepting non-European settlers. While the government in Ottawa insisted on the refugee policies being an aspect of the partition of Palestine, which showed it to be a caring and peacekeeping nation, the 100 Palestinian refugees admitted came from educated backgrounds.

As much as the country’s policy towards immigrants and refugees is now opening, research of contemporary immigration policies and polls also shows a bias not always related to race, but intellectual or economic advantage. A report by the Toronto Star notes that the children of immigrants are 12% more likely to attend university than children of Canadian-born parents. Another poll by the Globe and Mail indicated (although not substantially) that Canadians are more welcoming of economic migrants than refugees.

Finally, New Brunswick in particular is keen to accept immigrants of any kind. A 2015 CBC article indicates that immigrants who move to New Brunswick from abroad are more likely to leave than if they move to another city center like Toronto or Vancouver. With low rates of fertility and high outmigration, New Brunswick has made significant effort in the last few years to retain immigrants and provide ease of both education and opportunity for professional growth. This has included both refugees and economic migrants.

Biography:

Andrea Maria Dias is a B.Ed teacher candidate at the University of New Brunswick. She is a Canadian immigrant of Indian origin from the Middle East, and moved to Ontario in 2009. She loves Canada.

Further Reading:

1) http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/new-brunswick-clings-to-immigrants-as-hope-for-growth-1.3031839 “New Brunswick Clings to Immigrants as Hope for Growth”

2) https://www.thestar.com/news/immigration/2018/02/01/immigrants-are-largely-behind-canadas-status-as-one-of-the-best-educated-countries.html “Immigrants are largely behind Canada’s status as one of the Best Educated Countries”

3) https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canadians-have-different-attitudes-on-immigrants-versus-refugees-poll/article34179821/ “Canadians have different attitudes on Immigrants Versus Refugees: Poll”

4) https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/canadians/celebrate-being-canadian/teachers-corner/refugee-history.html “Canada: A History of Refuge”

5) https://www.pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/forgotten-experiment-canadas-resettlement-of-palestinian-refugees-1955-1956 Forgotten Experiment: Canada’s Resettlement of Palestinian Refugees, 1955-56 – Jan Raska

Miramichi Lumber Strike

Introduction: Miramichi is a small city located in the north-east of the province of New Brunswick along the Miramichi River. For many years, their main industry revolved around mining, lumber, fishing, and product distribution (Curtis, 1988). On August 20, 1937 approximately “1500 millworkers and longshoremen along the Miramichi River in northern New Brunswick struck 14 lumber firms” (Burden, 2006, p.1). This led to a halt in the “loading of pulpwood and lumber aboard five freighters at Nelson, Chatham Head, Douglastown” (Royal Canadian Mounted Police Headquarters, 1937, p. 352). Organized by the New Brunswick Farmer-Labour Union, a trade union that had been recently formed by Gregory McEachreon, the strike aimed to bring forth addressing issues surrounding increasing wages, shortening working hours, and union recognition. Workers were putting in ten-hour days and working for 17.5 cents an hour, which was deemed unacceptable by many (Frank & Canadian Committee on Labour History, 2013). During this time, the provincial government had recently enacted fair wage legislation. This was being highlighted during the strike and the workers were petitioning the government to take action on the issues they were bringing forward. The government refused to address what was being brought forth related to workers rights until the workers, primarily men, returned to work. “The strike ended on August 31 when a compromise settlement [was] worked out by mediators” (Burden, 2006, p.1). In 1938 the government took into consideration what was brought up in the Miramichi Lumber Strike as well as the Minto Coalfields Strike, October 1937, and re-evaluated their labour relations policy. Upon reflection, new labour legislation was introduced by the Government of New Brunswick in 1938 (Burden, 2006).

Biography: Kristen Ingraham is a University of New Brunswick, UNB, Bachelor of Education student and pre-service teacher. She previously completed a Bachelor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Leadership at UNB.

Further Reading:

1. Burden, P. (2006). Miramichi lumber strike. Histroica Canada. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/miramichi-lumber-strike/

2. Curtis, W. (1988). Currents in the stream: Miramichi people and places. Fredericton, N.B: Gooselane Editions.

3. Frank, D., & Canadian Committee on Labour History. (2013). Provincial solidarities: A history of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour. Edmonton: AU Press.

4. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Headquarters. (1937). Report on Revolutionary Organizations and Agitation in Canada, 868. Retrieved from goo.gl/yJsKZJ

Photo Sources:

- http://www.nbgsmiramichi.org/Album2/images/Miramichi%20Lumber-yard%20Horses%201890%27s.jpg

- https://tce-live2.s3.amazonaws.com/media/media/80691fa6-9b5a-4c82-a51d-0aaadaf68f77.jpg

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/timber-trade-history/

- http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_W06OeewCRS4/RjoaDOzplWI/AAAAAAAAABA/eUJsBePLsVg/s320/oldlumbercamp.jpg

Women's Political Rights in NB

Women’s Political Rights and History in New Brunswick

Introduction: The women’s rights in New Brunswick is something that is not often talked about in the school history curriculum. In New Brunswick, in the year 1834, the word male was entered into the election law to really show that women were explicitly excluded from the election process. Women who were independent were considered a threat to religious and cultural communities. In Saint John, New Brunswick the “Women’s Enfranchisement Association of New Brunswick” was formed in 1894 and it would be another 25 years before the women of New Brunswick would have the right to vote in a provincial election, thought it was still only if you were not a homemaker because you had to pay taxes and own property to vote in an election. It was not before 1934 that women were allowed to run for office and the first woman to be elected to the legislative assembly was Brenda Robertson in 1967. In 1948 Edna Steel was the first woman to be elected in office in New Brunswick; she was elected to the Saint John City council. In Port Elgin in 1959 the first female mayor, Dorothy McLean was elected. In 1966 the criteria for voting changed to only age (18+) and residence; therefore, all women were given the opportunity to vote.

Biography: Rachel Prosser is a Pre-Service teacher at the University of New Brunswick, living and studying in both Fredericton and Saint John, New Brunswick. After she graduates in June, she will start working as an elementary school French Immersion teacher in Anglophone School District South in September 2018.

Further Reading:

1. The elections NB website shows has a lot of good reading on not only women in politics in NB, but also many other interesting facts such as First Nations People, and religious beliefs (i.e Catholics could not vote until 1830, and after they still had pledge allegiance to the Protestant King and his heirs): http://www.electionsnb.ca/content/enb/en/about-us/history.html

2. The following website shows the statistics for women in politics in New Brunswick throughout the years: https://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2011/Everitt.pdf

3. On the Canadian encyclopedia, you can find information about Women’s suffrage in Canada; therefore, all of the provinces: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/suffrage/

4. This document published by the New Brunswick Advisory Council on the Status of Women has many interesting facts on many different people. http://www.wbnb-fanb.ca/docs/hints/Celebrating%20Achievers%20Quiz-En.pdf

5. If you would like to read more on some of the prominent women in New Brunswick Politics: Frances Fish (First Female to run for office in 1935): https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JNBS/article/view/18735/20494 and http://nsbs.org/frances-lilian-fish Brenda Robertson: http://www.gnb.ca/cnb/news/iga/2004e0833ig.htm

Discrimination Against Chinese Immigrants

Discrimination against Chinese Immigrants

Introduction:

Chinese immigrants were exploited and strongly discriminated against throughout Canadian history. They began to immigrate from China within the late 1700s due to floods, which made it hard to grow crops, and wars, which created poor and unsafe living conditions.

The Chinese immigrants moved here in search for a better life, but they faced a great amount of prejudicial treatment. They were considered inferior and unable to assimilate into Canada up until the mid-late 1900s. They were alienated from society, restricted of the right to vote, and exploited for cheap labour in poor working conditions. (Chan, 2016)

One of the most brutal exploitations of Chinese immigrant workers was for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Canadian Pacific Railway was built between 1880-1885 in order to connect the West Coast (starting in Port Moody, B.C.) to the East Coast (ending in Montreal, Quebec). (Building the Canadian Pacific Railway, n.d.) This was at the expense of over 15,000 Chinese immigrants who were made to work on the most dangerous parts of the railway, for very little pay. They made $1.00 per day, in comparison to the white Canadian workers, who made $2.50 per day. (Building the Canadian Pacific Railway, n.d.) In addition, the Chinese also had to pay for their food, clothing, transportation, and cooking and camping gear. They also received very little medical aid, and depended widely on herbal medicines. Many died due to the poor working conditions which included dynamite accidents, landslides, cave-ins, mal-nourishment, fatigue and lack of medicine. There is an estimated death count of 600 to 2,200 workers. (History of Canada's early Chinese immigrants, 2017) The deaths were poorly tracked due to lack of care and responsibility, and most families weren’t even notified of the deaths.

In 1885, after the railway was complete, Canada implemented a discriminatory $50 "head" tax on Chinese immigrants entering the country (this fee only applied to this ethnic group), which then went up to $100 in 1900, and further increased to $500 in 1903. (Chan, 2016) On July 1st, 1923, a legislation passed that banned most Chinese immigrants from entering Canada, this date is now known as “Humiliation Day”. (Chan, 2016) Only four classes of Chinese immigrants were allowed in Canada after this legislation: diplomats and government representatives; children born in Canada who had left for educational or other purposes; merchants; and students. (Dyk, Gagnon, MacDonald, Raska & Schwinghamer, n.d.) Legislation was finally repealed in 1947 (Chan, 2016), and since then the Chinese population, and diversity, has greatly grown within Canada.

Biography:

Marissa Simard is a currently enrolled in the Bachelor of Education program at the University of New Brunswick, living and working on unceded and un-surrendered Wolastoqiyik territory. She is a Pre-Service teacher at Liverpool Street Elementary School, and will be graduating in October 2018.

Further Reading:

1. Building the Canadian Pacific Railway. (n.d.). Retrieved February 16, 2018, from https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/settlement/kids/021013-2031.3-e.html

2. Dyk, L. V., Gagnon, E., MacDonald, M., Raska, J. & Schwinghamer, S. (n.d.). Chinese Immigration Act, 1923. Retrieved February 16, 2018, from https://www.pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/chinese-immigration-act-1923

3. Chan, A. (2016). Chinese Head Tax in Canada. Retrieved February 16, 2018, from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-head-tax-in-canada/

4. History of Canada's early Chinese immigrants. (2017). Retrieved February 16, 2018, from https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/history-ethnic-cultural/early-chinese-canadians/Pages/history.aspx

5. Lavallé, O. (2018). Canadian Pacific Railway. Retrieved February 16, 2018, from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-pacific-railway/

6. The Chinese Experience in British Columbia: In 1850 - 1950. (n.d.). Retrieved February 16, 2018, from https://www.library.ubc.ca/chineseinbc/railways.html

Notes:

1. Image of Chinese Immigrants working on the CPR was retrieved from http://www.kamloopsnews.ca/opinion/letters/how-many-chinese-died-building-the-cpr-1.1232831

2. Image of the Canadian Pacific train was retrieved from http://www.cpr.ca/en/cp-shops

3. Image of Chinese Immigrants at their campsite was retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/railway-history/

Women in NB Politics

Women in Politics in NB

Women deserve to have their voices be heard in an equal manner to men in the provience of New Brunswick. For the purpose for this inspiring poster assignment I have chosen to tackle the topic of women in politics in New Brunswick (NB) and particularily Elsie Wayne and the Women for 50% project.

Elsie was elected mayor of Saint John NB in 1983 and served as member of the House of Commons from 1993 until 2004 (CBC News, 2016). Elsie passed away in August 2016 but was an inspiration to anyone she made contact with and was never afraid to speak up for what was right (CBC News, 2016). In Elsies time women in politics were even more unknown then they are today.

The other area that peaked my interest for this assignment is the Women for 50% movement where women are pushing the New Brunswick government for equal gender representation within the government (Global Politcs, 2017). Currently, only 8 of the 49 MLA members in the province are women (Global Politcs, 2017). The mother of the founder of the Women for 50% project was a former president of the New Brunswick Liberal Association and gave 7 female candadits for the election in 1987 $100 each to buy the proper shoes to go door to door prior to the election (Global Politcs, 2017). Each of these women won that year. I thought this was neat because it shows the confidence and womens leadership was a trend within their family which is important for us to have in our province.

Biography Alyson VanSnick: I am an early childhood educator and a future elementary school teacher who hopes to instil confidence and leadership skills into every student she teaches. I hope to encourage my female students to fight for their own rights and to be advocates for themselves and their communties. By bringing attention to women in politics in New Brunswick I am able to give a voice to the idea that women deserve to be represented equally in politics.

References and Further Readings

Cave, Rachel. (January 2017). “Work begins now to elect more women to legislature in 2018”. CBC News New Brunswick. Retrieved from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/gender-parity-new-brunswick-legislature-2018-1.3931137

Cromwell, Andrew. (January, 2017). “NB group Women for 50% pushes for gender equality in government”. Global News New Brunswick. Retrieved from: https://globalnews.ca/news/3175212/nb-group-women-for-50-pushes-for-gender-equality-in-government/

McHardie, Daniel. (August, 2016). “Elsie Wayne, Former PC MP and Saint John mayor, dead at 84”. CBC News New Brunswick. Retrieved from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/elsie-wayne-obit-1.3732050

New Brunswick Advisory Council on the Status of Women. (2010). Women in the house: A reader on New Brunswick women in the Legislative Assembly. Fredericton, N.B: Advisory Council on the Status of Women.

The Yard

It is incredible how a place undergoes tremendous changes over time. Today, in New Brunswick, Rexton is a quiet village built around the Richibucto river where you can see fishing boats leaving the wharf to go lobster fishing, or small recreational crafts sailing in the summer. However, in the 1800’s, it was home to an extensive and reputed tall ship building industry. The scenery would have been very different than today with those majestic vessels sailing graciously in the harbour.

It was in 1816 that John Jardine, along with his brother Robert, came from Scotland to settle by the beautiful Richibucto River. By 1825, they had established an impressive ship building and lumber industry. The shipyard was at a very unique location, on the turn of the river, permitting a monitoring of the to-and-fro of sail boats. While Robert Jardine moved in Upper Canada a decade after, John Jardine, also called Old Jock, kept the flourishing industry running. His nephews, John and Thomas, followed Old Jock’s example by also becoming shipbuilders and developing their own successful company. Over a few generations, the Jardines built over 100 majestic tall ships. They were well known and reputed ship builders.

A community grew around John Jardine industries. It began as The Yard and grew into a village named Kingston in 1841. It was in 1901 that it became renamed as Rexton. Today, the land where John Jardine’s shipyard was established is still warmly called The Yard by the community. A tall ship monument called “Shipwreck” has been erected near the site to commemorate the ship building history of the region.

Chantal Vautour is a pre-service teacher living in the community of Saint-Ignace, just 20 km from Rexton. She has always been fascinated by tall ships and the rich history of the region.

For more information, visit:

http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=4668&pid=0

http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=4493

http://www.villageofrexton.com/history/ship-building/

http://www.genealogy.com/forum/surnames/topics/jardine/9/

http://www.bonarlawcommon.com/RRHS.html

Visit the Richibucto River Historical Society Museum located at the Bonnar Law Commons in Rexton

The Oxbow

I grew up alongside Metepenagiag Mi'kmaq Nation almost my entire life but never learned anything about the reserve and the people that lived there. The Miramichi river is an incredible resource and has been for thousands of years. It is mostly my fault that I have never taken the time to look into finding history books about Mi’kmaq culture and the history of the people on the river. I am lucky enough to have grown up on the river and the more I do readings the more I find a whole new appreciation for the world that I was privileged to live in.

When I started to research for this project I knew that my focus was going to be on the Red Bank area. It didn’t take me to long to find out about the Oxbow and I knew I had to investigate more about it. The Oxbow for my entire childhood was a water hole, it was an awesome place to go swimming because it was an inlet from the river and shallow enough that the waters would get warm on a hot day but deep enough that you can have fun. So when I realized that the Oxbow is a site for one of the oldest communities in Canada! I was shocked. Are you telling me that the place I would go to on weekends holds one of the richest histories in Canada? That it was one of the largest First Nation archaeological finds in history? It is frustrating. I wish that I was taught this in school. My school is only five minutes away and it would have been an incredible opportunity for us to understand the local history around us and could have created a respect among the students. But I should have found this out on my own; it’s ridiculous that I let this history sit under my nose for so long. It was a wake up call for me that I need to be more vigilant in my research work and that I need to take it upon myself to look out for information and ask important questions.

Biography: My name is Sam Wakefield. I am a person who is trying to be critical of my current knowledge of the local history around me with a focus on the Indigenous peoples. I grew up as a racist and regret the things that I have said and the lies that I thought. I am a better person now but realize that I have a long way to go to become an effective educator. I am going back to Miramichi to teach and I pray that I can make an impact on the lives of students and break a vicious cycle that continues there.

Further Readings:

Maliseet & Micmac First Nations of the Maritimes

By: Robert M. Leavitt (The entire book is interesting but pages 157 – 165 include information about the Oxbow and have photos of the archeologically findings)

Miramichi Papers

By: W.D. Hamilton (Chapter 7, pg. 77)

http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/thc-tpc/pdf/Arch/MIA39english.pdf - This PDF includes information about the findings at the Oxbow.

http://www.gnb.ca/0007/heritage/oxbow/oxbow.html - This website is an easy reading resource, limited information but gives you a good understanding of the importance of the Oxbow.

Slavery in New Brunswick

Introduction: When we think about slavery in Canada it is often that we think of our country as a place where African-American slaves were able to escape to freedom. This learning commonly leads us to believe that Canada never engaged in slavery but this idea is not completely correct. There is evidence of slavery existing in both the Maritimes, and more specifically in New Brunswick.

“Shortly after the arrival of the loyalists, in 1784, the Province of New Brunswick was created to satisfy those loyalists who had moved to the St. John and who did not wish to be governed from Halifax. With the loyalists were several thousand Black people. Some came as slaves or indentured servants, others as free Blacks or mack loyalists. In documents, the loyalists always preferred to refer to their slaves as “servants”. However, the status of the majority of Blacks who were listed as “servants” was certainly no different than that of those listed as slaves.” (MyNB, 2015)